Takeoff speeds rule everything around me

Not all short timelines are created equal

A decade ago, debates about AI x-risk often centered on AGI timelines. Was it over a century away, or was it plausibly as soon as 20 years? Today, even people relatively skeptical of x-risk often have crazy short timelines like ten years or five years or negative two months. So what accounts for the vast remaining disagreement on the level of imminent risk and the appropriate policy stance toward it?

I think it’s secretly still mostly about timelines. These days, I suspect many people who aren’t particularly concerned about x-risk combine very short timelines to AGI1 with very long timelines to AI transforming the real world — in other words, they believe takeoff speed will be very slow.

The classic definition of takeoff speed is the amount of time it takes to go from AGI to superintelligence,2 but both of those terms are very slippery. And it’s hard to articulate exactly how “super” an intelligence we’re talking without specifying what impressive feats it should be able to achieve in the real world. Instead, I think it can be more illuminating to operationalize “takeoff speed” with respect to outcomes in the external world caused by AI.

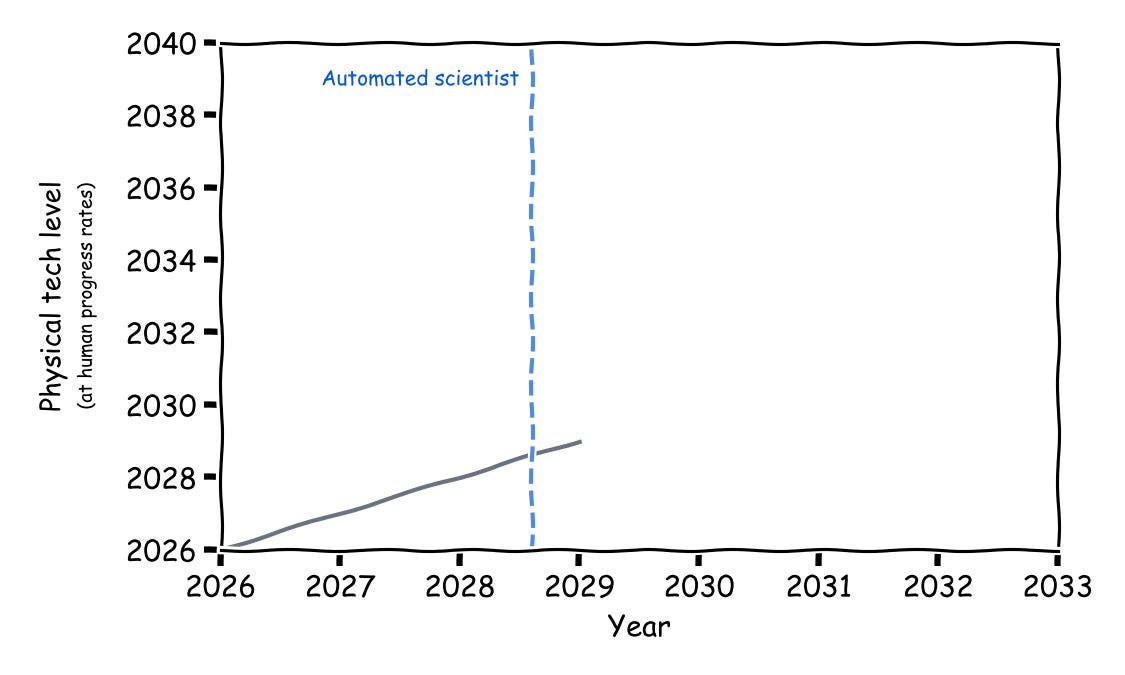

One crucial yardstick for takeoff is the speed of progress in physical technology.3

Consider the average rate at which scientists and engineers have been making new discoveries or improving the efficiency of existing processes across a wide range of hard-tech fields (hardware, batteries, materials, industrial chemistry, robotics, spacecraft) over the last 20 years or so.

Now suppose that sometime in 2028, we develop AI that can automate all the intellectual work that all these scientists are doing across all these fields. How many “years of progress” (at the old human-driven pace) will these fields make each calendar year?

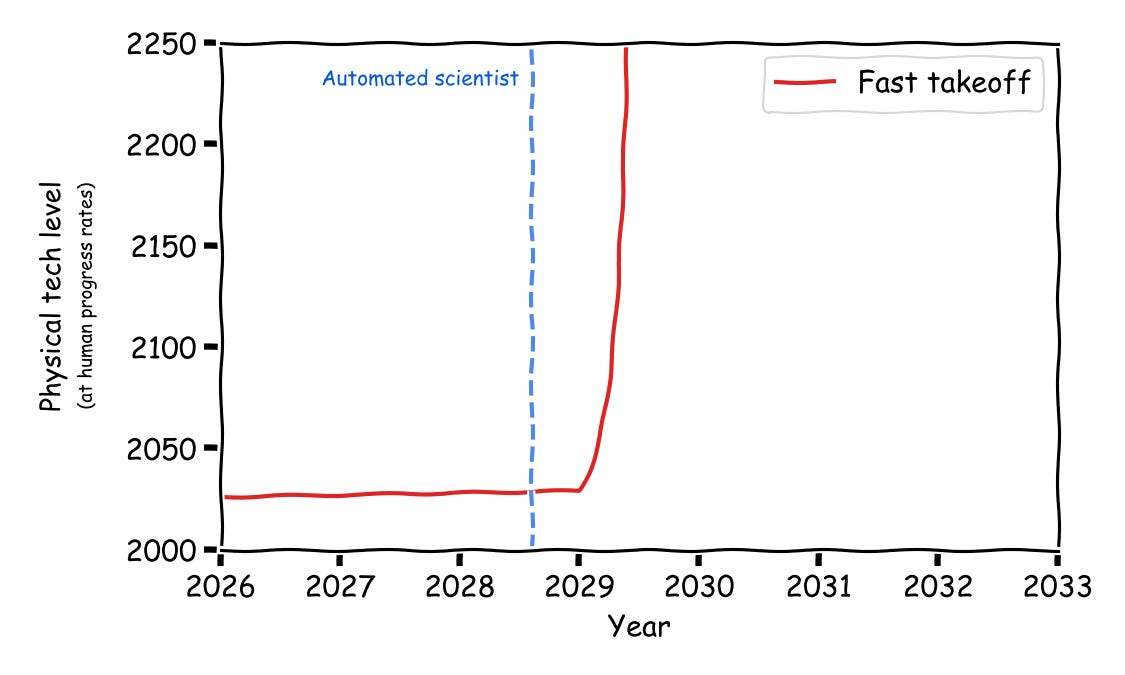

Here’s a classic “fast takeoff” view:

On this view, once AI fully automates further AI R&D, this will kick off a strong super-exponential feedback loop that leads to unfathomably superhuman AI within months. While that software-based intelligence explosion is going on, you don’t really see physical technology improve all that much.4 But once we have this god-like AI, it’ll take only months or weeks or days to create sci-fi technologies (molecular nanotechnology, whole brain emulation, reversible computing, near-light-speed spacecraft) that would have taken centuries at human rates.

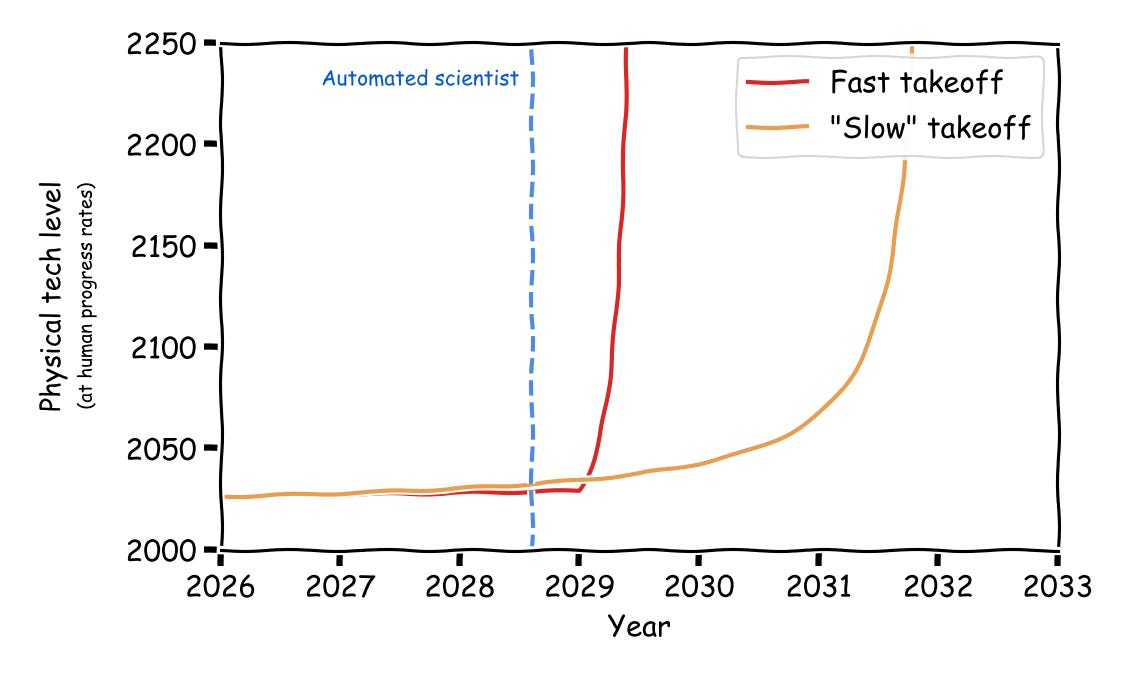

In contrast, here’s a view that would be considered a “slow takeoff”, again conditioning on full cognitive automation of science in mid-2028:5

On the “slow” takeoff view, there is still a super-exponential feedback loop of AI-improving-AI. It’s just that we need to incorporate physical automation of the entire AI stack to get that feedback loop going, so it’s more gradual (and we actually see physical signatures before we get the full automated scientist). But even “slow” takeoff still means that we go from automated science to an unrecognizably sci-fi world within a matter of years.

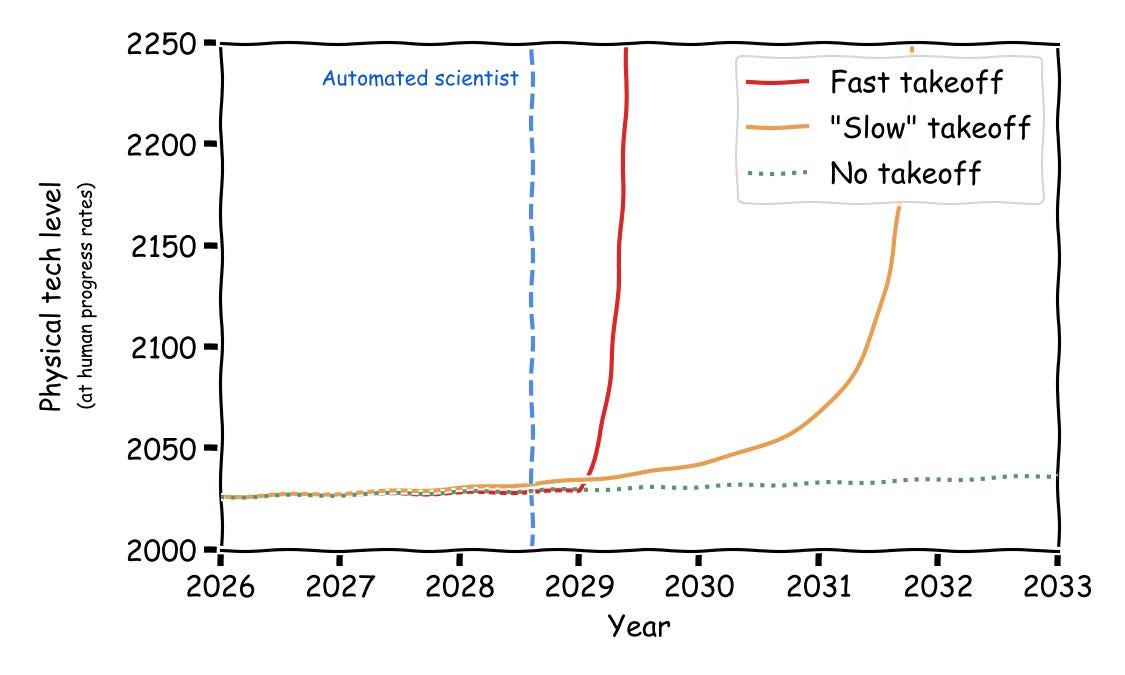

Meanwhile, I suspect most x-risk skeptics think that AI automating scientific research won’t be that big a deal. Perhaps it makes R&D go modestly faster, or perhaps AI automation is necessary just to keep us going at our previous pace, when otherwise we would have stagnated. They think there will be no takeoff at all.

This one parameter underlies a huge range of disagreements. Will the country that first develops AGI gain a “decisive strategic advantage” — the ability to impose its will on everyone else? Well, if a six month lead in AI translates into a centuries-long lead in weapons technology, probably. Could misaligned AI systems drive humanity extinct? If they can trivially develop a superplague to wipe us out and upload themselves into self-replicating nanocomputers to survive without us, then sure. Should we try to slow down AI? If it means that we get a year or two to absorb the impacts of a world with technology from 2100 before we have to deal with technology from 2200, then yes please.

In my view, this has always been at the heart of the disagreement, and it still is. But now that some level of powerful AI (say at least an 8 on Nate Silver’s Richter Scale) feels around the corner to doomers and skeptics alike, the deeper disagreement about just how powerful it’ll get and how quickly has been obscured. Some people think AGI is the next innovation that allows us to sustain 2% frontier economic growth a little while longer, or maybe add a half a percentage point more. Others think we are t minus a few years from first contact with an unfathomably advanced alien species, entities we would view as nothing less than gods.

Or at least, something they call “AGI.” As I discussed last time, I think the definition of AGI is often unproductively watered down. The people with the very shortest timelines (e.g. 1 or 2 years) are disproportionately likely to be forecasting a milder version of “AGI,” which in turn exaggerates how long they believe the takeoff period will be from AGI to radical superintelligence.

This is the definition given by Nick Bostrom in his 2014 book Superintelligence.

Another important real-world yardstick of takeoff is economic output, or gross world product. This is the operationalization used in this 2018 blog post by Paul Christiano and Epoch’s GATE model, and is the central operationalization used in Tom Davidson’s 2021 takeoff speeds report (though that report also models several other metrics like software and hardware; you can play with the model here). This is also really important, but it introduces some complications that aren’t essential for the basic argument.

If this graph was a graph of the cognitive capabilities of AI systems, it would be rapidly but smoothly growing over the whole period from 2026 through 2029, like the AI Futures Project’s takeoff model. But I think the graph of physical technology better illustrates how the takeoff will feel to people outside AI companies.

I wanted to illustrate different views about takeoff conditional on a fixed timeline to fully-automated science, but in reality if you have slower takeoff speeds, you probably also have longer timelines to that initial milestone. (And there would be room for even more acceleration prior to full automation.)

I've seen this view advanced before, that the only reason optimists aren't scared of ASI is that they secretly don't believe in rapidly accelerating technological progress, but it's false, at least for me. It _would_ be true if I believed "evil is optimal" (as Richard Sutton summed up the viewpoint), so that an ASI system would agree with Yudkowsky that its best course of action is to exterminate humanity to harvest its atoms. But I don't agree that evil is optimal, for a number of reasons.

To be clear, I'm somewhat skeptical of the "slow takeoff" curve plotted here. (It may not be physically possible, no matter how smart an AI system may be.) But if that speed of progress were to occur, I expect that it'd be a good thing and risk-reducing compared to slower progress.

I guess the next logical question is what evidence / frameworks can we use to reason about take-off speeds?

Biological anchors and scaling laws were solid ways of reasoning about intelligence progress. But they don’t seem to tell us much about take off speeds?